Illinois School for the Deaf Main Building (Courtesy of 1969 Illinois Advance)

By Trudy Suggs

PART 1 (Click here for Part 2)

It was going to be a splendid trip. Forty boys from the Illinois School for the Deaf (ISD) were headed to Chicago to watch a Chicago Bulls game. In past years, they had gone to watch the St. Louis Hawks and visit the St. Louis Arch — both a mere 90-minute drive away — but the Hawks had moved to Atlanta, so Chicago it was.

The boys eagerly packed their suitcases. On Saturday, January 24, 1970, they climbed onto the school bus; it was nothing fancy, just your standard yellow school bus with green seats that bounced so hard at times you felt as if you might shoot through the roof.

The ride took nearly five hours up I-55. The boys joked and talked excitedly about what they would see. For some, it was their first time to the big city. They came from rural towns, and had only heard gangster stories about the city. For others, it was their hometown. Chaperoning the trip was Zeke Beranek, a teacher and coach who spoke crisply as he signed each word.

They arrived in blustery Chicago and checked into the Conrad Hilton Hotel on Michigan Avenue, a stately building overlooking Lake Shore Drive and Lake Michigan. The boys were abuzz with excitement as they explored their fancy surroundings, and went sightseeing. Beranek immediately chose older kids as leaders to help the younger kids. He collected each room’s key in the event of an emergency and so he could wake them up for church the next morning.

Four boys were assigned to each room on the ninth floor; Beranek roomed with the school bus driver. Most of the boys slept in one wing, with the remainder spilling over into another wing. Charles Bright, a 17-year-old sophomore, was with roommates Bruce Kennedy and Robert Perry as they flirted with hearing girls from Ohio in the fifth-floor lounge. When some hearing guys came up, unhappy with the unsolicited attention the girls were getting, the boys went back to their room and headed to bed.

David O. Reynolds, a 16-year-old sophomore from rural Kankakee, was having the time of his life fooling around with his friends in the hallways and elevators, as teenagers are apt to do. “I was a huge Chicago sports fan, and always read the newspaper every day,” he said, “and I was so excited for the game.” Reynolds decided to go to bed and get ready for the next day — but not before he read that day’s newspaper.

Bruce Kennedy (Courtesy of 1970 Illinois Advance)

The Beginning of a Nightmare

At 3:00 a.m., feeling unusually warm, Bright woke up. He walked to the window and opened it before walking to the door and propping it open. Even in the 1970s, this was still a bold move in the big city. The dangers of leaving the door wide open didn’t occur to Bright, a naïve small-town kid who was the sixth of eight kids from Moweaqua, 20 minutes south of Decatur. Bright noticed it was rather warm in the hallway as well, but climbed back into bed without a second thought.

Two hours later, the fire alarms finally went off. Back then, hotels weren’t required to provide visual fire alarms, so none of the deaf boys had any way of knowing unless someone woke them up or they smelled the smoke. Kennedy, who was hard of hearing, shook Bright awake, saying, “Fire! Fire!” Groggy from deep sleep, Bright saw the room filled with smoke. Seeing that Kennedy was ready to run from the room, Bright clutched Kennedy’s wrist and said, “Don’t go!” But Kennedy wriggled free and ran out, never to be seen again.

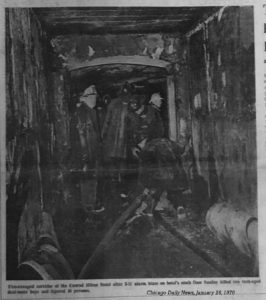

The ninth-floor corridor was the most damaged of all the hotel floors.

Bright, who had become deaf from spinal meningitis and had terrible balance as a result, began coughing and choking on the smoke. He later realized the room was so filled because he had his windows open, which sucked in smoke from the hallway. He saw Albert Jones, another roommate, running into the wall three times, desperately looking for the door. Although the sun had begun to rise, the room was pitch black.

Bright panicked. “I had never experienced a fire drill at school and I didn’t know what I was supposed to do,” he recalled. He ran to the bathroom to grab a wet towel, and crawled back to the window. He tied three bed sheets together to lower out of the window, thinking maybe he could climb down somehow. The sheets immediately dropped to the ground below, and Bright began to sob, fearing death was inevitable.

Room 909

Reynolds was soundly sleeping when roommate Mike Davis tapped him awake. Smoke had already seeped into the room. “I woke up coughing, and ran to the door to open it,” Reynolds remembered. “That was a big mistake, because there was a wall of blackness right there. I remember this clearly. There was just this black wall, and I was so confused. I stumbled backwards and fell down.”

Reynolds began crawling, recalling a movie he had watched at school about how to stay safe by crawling under the smoke. “I thought I could easily beat the smoke,” he said. “But even as I crawled, the smoke still came down on me.” He figured he would open the two windows, but they had been illegally sealed shut with insulation tape. After giving it a few tries, he knew it was futile.

“I fell back on the floor, and put a pillow over my face. I couldn’t breathe, and I could feel the smoke filling my lungs,” Reynolds said, lost in thought as he remembered the sensation. He had no idea where his roommates were, but became focused on saving himself. “I got up and went to the window again, and tried again to open it to no avail.” He desperately pulled down the curtain rod and tried to break the window with it. He succeeded, creating a baseball-sized hole. “I put my mouth to that hole, and it was the very first time I had ever given up. I remember thinking, Okay, God, it’s now my time. I have good parents and good faith. And then I passed out.”

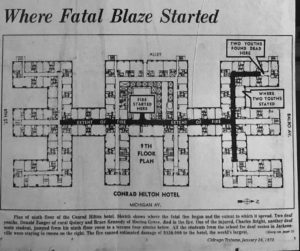

Floor map

Donald Zanger (Courtesy of 1970 Illinois Advance)

The Second Fatality

In a corner room, eighth grader Dale Saline of Rio, near Iowa, was about to celebrate his birthday. He had gotten special permission from his parents to go on this trip, and roomed with high schoolers Donald Zanger, Michael Ubowski, and Dennis Lovstad. “At about 5:30 or 6:00, I woke Donald up,” Saline said. “Donald immediately ran out in a panic, and I woke Mike up as well. He did the same, and ran out.”

Saline, unsure of what to do next, put a wet towel by the door. Fortunately, Ubowski returned a short time later, and a lost Danny Thomas wandered into their room. “We weren’t that close to the elevators where the fire started, so it wasn’t as bad as in the other rooms,” he said. “We waited for the longest time and I was really scared. A fireman tried to get a ladder up to us, but it only went up to the seventh floor and we were on the ninth floor.”

Some time later, their door suddenly burst open. A fireman had arrived to lead them to safety. As they made their way through the hallway, Saline kept tripping over the many hoses on the floor. They took a service elevator to the kitchen where all the others had congregated.

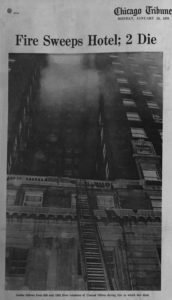

Charles Bright jumped from his ninth floor room onto the concrete terrace, located at the top of the ladder in this photograph. Miraculously, he survived.

Jumping to His Future

Meanwhile, Freeman Harper, 17, of Quincy, was in another room with three other boys. Their room was near the elevator shaft where the fire originated, so their room filled with smoke quickly. “I suddenly woke up, terrified, and screamed in fright,” Harper said. Unlike Reynolds, he and his roommates opened two large windows and waited approximately 45 minutes until firemen rescued them.

When Harper was safely on the ground, he and the many others looked up at the hotel searching for survivors. He watched in horror as Bright climbed out of his window.

Bright, still sobbing, made a split decision. He scampered onto the ledge, and saw a woman on a lower floor waving, “No, no! No!” He lowered himself, his fingers tightly gripping the edge of the ledge, and hung on for dear life. He looked down and then back at his window that was emitting more smoke than ever. He could feel his fingers slipping, so he let go. “I blacked out and can’t remember anything after my fingers left the ledge,” he said.

“I screamed, ‘Oh, my God!’ and watched his body fly down the four floors,” Harper recalled. “I remember his lifeless body on the balcony and fearing the worst.” Bright crashed into a fifth-floor concrete terrace and vaguely remembers waking up and trying to take a few steps before falling to the ground where he passed out for the final time.

Firemen eventually carried Bright into a fifth-floor room, where he waited for an ambulance to take him to the hospital.

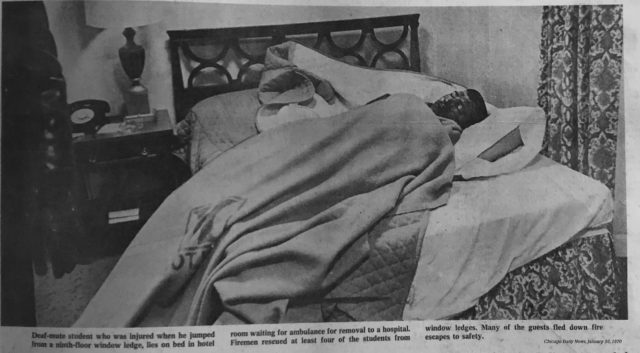

After Charles Bright fell four stories onto a concrete terrace, firemen carried him to a hotel bed. Miraculously, he survived the fall.

Fighting for Survival

Back in his room, Reynolds was regaining consciousness. He said, “I woke up, after I don’t know how long, because of the draft. I don’t think if I had stayed passed out for another minute, I would have survived.” The draft was coming from an opened window. Roommate Larry Peterson had ripped the tape off and then snapped open the window in a fit of super-strength. Reynolds scrambled to the window and leaned out. As he took deep, painful breaths, he looked in all directions, and saw others sticking their heads out of their windows as well. He also saw people making their way down fire escapes, and wondered if he could do that. He returned his eyes to his roommates, Davis and Peterson, and realized that their faces were completely covered in soot. He said, “There were lines going from inside their noses to their lips. It was surreal, and I knew I probably had them, too.”

The boys quickly talked about what to do. They also worried about where their other roommate, Mike Tonner, was. Tonner had cerebral palsy, and had run out into the hallway in a state of panic. Just then, the boys realized that the open door and open window created a cross-breeze that helped clear the smoke. The wind slammed the door shut, and Reynolds said, “Against all common sense, I ran to open the door. I could see that same wall of smoke, but the open door helped clear the room of smoke.”

Michael Tonner, who had CP, was carried to safety by a fireman and taken to the hospital.

At that moment, Tonner returned, badly shaken up. The soot-covered boys grabbed him and brought him inside the room. The room was quickly becoming cold from the window, so Reynolds — at that point dressed only in his underwear — went to put on his clothes and his glasses. Since he could speak and hear a bit, Reynolds picked up the rotary phone and spoke to whoever was on the other end, “Please come get us, we’re trapped!” He had no idea if anyone was listening.

The boys stood at the window, screaming at people and waving to other people trying to get some help. By then, it was past 6:00 a.m., and daylight had almost fully arrived. Davis was confident that they would be safe by then, reasoning that Reynolds had called for help so people knew they were in that room. They waited for what seemed like a very long time when suddenly Peterson said, “I can feel footsteps!”

Sure enough, the door opened and a big, burly fireman came in, coughing. Reynolds immediately pointed to Tonner and said, “He has CP, he can’t walk.” The fireman easily swung Tonner over his shoulder, and told the boys to follow him. “As we went down the hallway, thinking everyone else had died, I noticed that the hallway carpet was frayed from the fire. There was smoke billowing everywhere,” Reynolds said. The floor was also covered in water from fire hoses.

They walked down the long hallway, and Reynolds saw a splintered exit door. Reynolds, Davis, and Peterson ran to the door as the fireman went in a different direction. “We never saw the fireman again,” Reynolds said. They ran down the fire escape to safety. Reynolds said the first thing he noticed when they got outside was how cold it was — this was Chicago in January after all — and then he thought, “I’m alive! I’m alive!” People were waving at them, and they had to jump a few feet from the bottom of the fire escape to the ground.

Fire trucks were parked everywhere they looked, their lights flashing like no tomorrow. Water hoses were blasting cold water in every direction. “It was like a movie, that’s the best way I can explain it,” Reynolds said. He stood there for a few minutes, taking in the stunning event he had just survived.

“We all had suddenly become men. And we weren’t ready for that.” – David O. Reynolds

“We all had suddenly become men. And we weren’t ready for that.” – David O. Reynolds

Collecting Themselves

As Reynolds stood figuring out what to do next, he was directed to a mailroom where the other guests were. As he walked towards the ISD group sitting off to the side, he saw how every face looked exceptionally sorrowful and sad. Looking at each boy’s grim, shell-shocked face, Reynolds realized something startling. “We all had suddenly become men. And we weren’t ready for that.”

Word had already gotten out that there had been some fatalities, but nobody knew for sure. Many had been whisked off in ambulances to area hospitals, and the rest kept checking on each other, making sure they all were okay. Reynolds, still coughing up soot, declined a trip to the hospital.

Details began coming together. The boys began ticking off names, trying to figure out who was missing and who was accounted for. They wrote back and forth with emergency responders. Saline, who had roomed with one of the two missing ISD boys (Donald Zanger), was interviewed by emergency personnel with Beranek interpreting. Shortly after that, Beranek left.

Firemen are shown examining the area where the fire supposedly started. Charred remains of furniture are visible in this photograph.

Information began trickling in. The fire had started in an elevator shaft on the ninth floor, and since that floor was undergoing renovations, there were furniture and other things piled up near the elevator, creating an extremely flammable area. Theories began piling up: Was it arson? Did the boys who got angry at Bright, Perry, and Kennedy throw a cigarette to start the fire? Or was it just an electrical failure?

“We were in deep shock, us boys. We couldn’t believe what was happening,” Saline said.

The boys sat there waiting for someone to tell them something and wondering what would happen next. Reynolds suddenly began to feel sick, and realized he probably should get some medical attention. He was quickly taken to an ambulance, where he put on an oxygen mask and was driven to a hospital.

There, Reynolds was told to put a tissue to his mouth and start coughing. He did, and was shocked to see piles of soot coming out of his mouth. His lungs had completely filled with soot, and his larynx had been burned by the smoke. He later would learn that he had blood in his lungs for several years because of this smoke inhalation, which caused him to have nosebleeds often for many years. After several hours sharing a hospital room with Albert Jones and Freeman Harper, a somber-faced Beranek appeared at their hospital room door.

Click here for Part 2. All photographs are taken from the Chicago Sun Times, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily News, the Illinois Advance, and the interviewees unless otherwise indicated. Special thanks go to Joan Engelmann and Rosa Ramirez.

Hi Trudy,

I am happy to see your new article posted!

Your wonderful articles always get my attention to read!

I was a high school science teacher during that school year and remembered it very vividly. Real sad that I lost a bright student, Bruce Kennedy. Thank you, Trudy, for sharing the story. Will look forward to the part 2.

Never knew this!! Thank you for writing/sharing!

I suppose go to ISD in Jan 1970 as new student and I moved to Chantel AFB , IL from RAF Lakenhealth, Suffolk England . I was excited to new school that’s week but somehow ISD main called my parent and have to postponed to Feb 1970 cuz due funerals. I never met two guys who died.