I first saw the term DEAF-HEART at an interpreting conference back in the early 2000s. There was a heated discussion in a workshop, and an interpreter stood on stage saying how important it was to have DEAF HEART—she signed “deaf” over the heart. My friend, a top-level interpreter, quickly looked at me to see how I reacted. I naturally was caught off-guard by that sign and turned to her, saying, “What the…?” She giggled at my reaction, and said, “Yeah, I know. A new phrase that’s catching on.”

I had a sick feeling in my stomach, although I didn’t understand quite what bothered me so much about the phrase. It didn’t help that the newly certified interpreter on stage was not yet fluent in American Sign Language. Later that day, I chatted with other deaf people at the conference and discovered that I wasn’t the only one bothered by this phrase.

Fast forward to the 2013 Street Leverage event in Atlanta, where this term seemed to be all the rage. Even Deaf presenters stood onstage and talked about what DEAF-HEART meant. I wanted to write about this phrase then, but I still hadn’t quite pinpointed why it was such an abrasive phrase to me. Over time, I talked to many people: interpreters, Deaf people, CDIs, and everyone else in between. The same messages kept emerging: they, too, didn’t like the phrase but weren’t sure why. The select few (all hearing) who did like the phrase said the phrase made them feel like they belonged to the Deaf community.

Let’s explore the history of this phrase. While there’s no hard evidence of exactly when DEAF-HEART began being used, the phrase has been around at least 15 years, based on the first time I saw it. I spoke with Lewis Merkin, CDI, who said he and a group (including CDIs Jimmy Beldon, Alisha Bronk, Janis Cole, Kristin Lund, and Priscilla Moyers) had met in December 2008 as part of a Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) Deaf Members in Leadership committee meeting. As reported in the Spring 2009 issue of the RID VIEWS:

The best approach to reminding members of the value of an “of Deaf” perspective is to create an atmosphere where this occurs naturally. We discussed “Deaf Heart” [sic] concepts (ASL, visually accessible information, collectivism vs. individualism, culture, history, CODA input, etc.) and looked at how this can be incorporated (at the 2009 RID National Conference, collaborating with NAD, CIT and ASLTA to incorporate allies principles into interpreter training program curricula, revisit the wording of RID’s strategic challenges, etc.).

In that same issue, Bronk wrote in “Interpreters: Gatekeepers for the Deaf Interpreter Community”:

We should all be open to sharing our experiences, frustrations and joys of our work in an effort to improve ourselves and our field. We know that deaf and hearing interpreters, working in teams, can provide the best service to many Deaf community members, enhance all of our skills, and bring what the Deaf community calls “Deaf-heart” [sic] back into our field.

Merkin told me, “I know when we were talking about it, it was to find a way of explaining what we considered positive traits. How it’s been co-opted is another story.”

I continue to be uncomfortable with it for a number of reasons, and I continue to be surprised by how many people have expressed their discomfort with this phrase but are hesitant to share their discomfort for fear of backlash.

With the interpreting field becoming much more professionalized—not a bad thing, in any way—I find that more and more interpreters are trying to use different labels, including “having DEAF-HEART.” John, a friend I shared this article with said it best: “Without having the lived experience of being deaf, you may be able to identify various factors and experiences deaf people have on an intellectual level, but at the end of the day, you don’t have that personal experience.” This is true even for those who are hearing and have Deaf family members; while they may see the good and bad experiences of being a Deaf person, they don’t experience it firsthand.

I remember when I first understood this. Ironically, it was a hearing person who taught me this—a straight, white male who people love to hate: a police officer. Ken and I were co-teaching a course at the Illinois State Police Academy after two deaf men had been killed by police within a month’s span back in 1996. A high-ranking Illinois State Police administrator, Ken happened to be my graduate school notetaker and became a trusted ally and friend. We naturally joined forces, with our work leading to a statewide curriculum addressing how police should communicate with deaf people.

During a class, Ken asked the 60 cadets, “How many of you had met a deaf person before today?” Only five or six raised their hands, which surprised even me. He then asked me, “Trudy, how many times this morning did you have to tell someone you were deaf?” I mentally did the calculations, and said, “Five or six times.” It was only 10:00 a.m. when I gave that answer, and I suddenly understood just how much being Deaf shaped my life experiences, even for simple tasks such as getting gas or buying food.

This illustrates exactly why no matter how “Deaf” a hearing person may be or feel, that person will never have firsthand knowledge of the tension or even fear we have when we are in a situation involving communication. They can empathize, of course, but it’s a completely different experience when you’re actually living 24 hours a day as a Deaf person.

Another reason I bristle at DEAF-HEART is that it seems as if this is yet another way to try and gain entrance to the core of our community. Can you imagine telling someone, “That [white American] interpreter has ASIAN-HEART”? While it obviously is meant to be complimentary, it’s really not.

This is the crux of the problem for me: how interpreters consistently and continuously try to be as integrated into the Deaf community as they possibly can be. I can’t count how many times an interpreter or ASL student has excitedly said to me, “Wow! That person thought I was Deaf or had Deaf parents!” as if this was the highest praise available. And of course there are those who say, “That interpreter really does have a DEAF-HEART.” To me, this is an example of cultural appropriation—even if unintentional. I also recognize that many Deaf people promote this phrase without understanding the weight it holds. One Deaf interpreter said, “DEAF-HEART is like branding. By gaining this label, you’re branded ‘in’ with Deaf people.”

John, my friend, added, “To me, DEAF-HEART has a negative connotation because it implies that one does ‘goodwill.’ We do not need their goodwill, we need them to respect us and treat us equally. That’s it. Why isn’t having our respect enough? Why do we need to reward hearing people, who represent the majority, by giving them a name like DEAF-HEART when they are supposed to respect our culture and language, anyway?”

Yet it seems many hearing interpreters and deaf people have become enamored with the idea that it is necessary to be as Deaf as possible to be accepted in the Deaf community. This is not appropriate, nor true. There is absolutely nothing wrong with being an outsider who supports the Deaf community. You may ask, “But what about trust? How can we gain Deaf people’s trust?”

Ah, but there’s a word for this: ally. I think this word is so much more powerful than DEAF-HEART. Ally has been in use for years, and for good reason; most dictionaries define it as coming together for a common cause or purpose and in mutual respect.

One can be an ally and have access to the community by practicing that word’s meaning to the highest standards possible. John added, “To be a true ally, people have to practice humility, which means they do not tell Deaf people they have gotten our respect or share the praises they get from us. Humility and respect are what makes them true allies.”

Exactly. And that’s why I will always choose to work with someone who is sincerely an ally rather than someone who supposedly has DEAF-HEART, because to me, a genuine ally means someone who actually works with you to make something happen, shows respect, and understands better than anyone else that this is your experience.

Copyrighted material, used by permission. This article can not be copied, reproduced, or redistributed without the written consent of the author.

I have SOOO much I want to say. This vlog is the reason I give my workshop, “You’re Hearing… And That’s Okay.” You don’t NEED a Deaf heart because you HAVE a heart already. Its a human heart. And a human heart is capable of an incredible amount of respect. So have THAT instead. BRAVO!!!

-Jer

Thank you for publicly initiating this much needed discussion. I, too, dislike the phrase, “Deaf-Heart.” You nailed it with your thoughts about Ally & Ally Culture. Allyship work means that we do not go to marginalized individuals and inform them that we are their ally. Claiming that one has a Deaf-Heart feels like ally-culture, and creates tension– forcing us (attempting to) to accept the person before that trust has been earned. I also feel the phrase objectifies Deaf people- “I Love Deaf People” – as if we are a thing. Really appreciate your video– I know there will be a lot of resistance to this. Standing with you.

I think we are witnessing the beginnings of a new breed of interpreters who are in it for themselves, don’t follow Code of Ethics, and consider the hearing audience as their ‘customer base’ (such as Kevin, the ‘interpreter’ for Seattle theatre who now calls himself “Sign Language Artist”), OR who have an extreme need to be validated either by the Deaf community (in form of ‘Deaf heart’) or by the media (i.e., Kylie Kirkpatrick). I am seeing more and more of this new type of interpreter in the past couple of years, and I’m concerned.

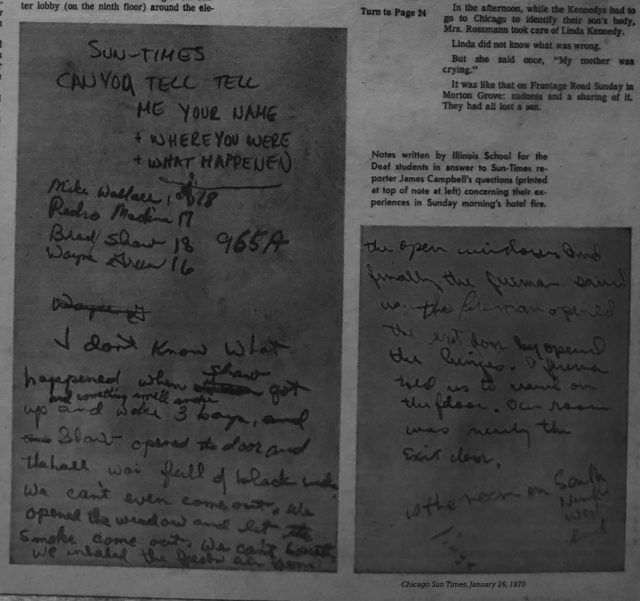

I thought of the Deaf-Heart issue few weeks ago when visiting my 75 year old Mom, we were chatting and she signed, “…. has no heart for Deaf people”. It brought back many conversations I observed growing up as many Deaf folks who are now in their 80s and 90s often referred this concept to hearing folks who know sign and are involved in Deaf community and regular hearing folks who don’t sign and know nothing or little about Deaf community, for example; “that guy doesn’t sign or know much about Deaf folks but has good heart for Deaf people” and “that interpreter has no heart for Deaf people”. That concept was around for decades but our parents got it right with how they expressed it and continue to do so. The term “ally” was not utilized back then but our older generation applied the same concept in a different way. Great article Trudy. Can’t wait to see my Mom and show her this article. :-)

Also a note- I read a bit too fast the first time around and missed it- nudging you to consider not including analogies to other racial groups. It is usually not equivalent and tends to be erasing of folks who have one or both identities (intersectional) being used in example – i.e. Asian Interpreters or Asian Deaf people.

Stephanie, I hope you saw my (unnamed) shout-out to you in the article. :) Thanks for your input last year on this topic–it really helped.

Trudy, thank so much for this. Sometimes it does feel a bit like peeling an onion; there will surely be people who, by stalwartly refusing the label of DEAF-HEART as you suggest, feel they’ve gained the same pseudo-insider status in the community as those who seek the label.

I’ve heard people raise the same issues with people from the outside calling themselves “allies”. We’re only known by our actions, and it’s really up to the in-group members to decide who’s their ally at any given moment. I stress “at any given moment”. I don’t believe one can determine oneself to be “once an ally, always an ally”, but I think that must be a little bit of the feeling behind claiming the label, at least by some.

Thanks again,

Aaron

Oh, and a question: Do you think it makes a difference for you if a Deaf person expresses the sentiment behind “DEAF-HEART, not as a single made-up sign, but just in an expression that has the sign “DEAF” followed by the sign “HEART”?

Really appreciate the points raised in this article. I, too, don’t like the term because of what it’s come to mean. In my opinion, it has come to mean an interpreter who was born to deaf parents and therefore is the only kind of person that can really understand being deaf. You are absolutely spot on in saying that person may have a better understanding, but they still don’t know. This version of the meaning also indicates that no person born to hearing parents can ever achieve this standard. I don’t believe that to be true and it also dismisses the concept that to be truly successful, a movement has to involve complete outsiders as allies.

Thanks, Trudy, for these comments. You don’t know me–and maybe a lot of your other readers/watchers don’t either. I’m hearing, was referred here by a Deaf friend. You stated things so well. What especially impressed me is your combination of frankness about things that bothered you without any trace of bitterness. That was VERY impressive. Personally, I felt respected by you, in the way you talked about hearing people. I appreciated the clarity you provided about how we hearing should seek to be humble, respectful allies to our Deaf friends rather than seeking a DEAF-HEART. Bravo!

Alison, can you explain more why we shouldn’t use analogies to racial groups? I agree that we shouldn’t do that if we say, “We experience oppression like women and Asian people experience oppression.” However, in this article, Trudy gives a hypothetical example that helps the reader understand why the phrase is culturally inappropriate. I do not see how the example itself could be harmful because it does not imply anything negatively about Asian people or Asian Deaf people, their culture, their language, and their experiences. I think that they would agree with us that they do not support the phrase, ASIAN HEART, if someone uses it. But, I am eager to understand more why it’s not appropriate and thank you for your time to respond to my question.

Thanks for a courageous and really timely piece on this issue. The current group of EUMASLI students – a Master’s degree run by Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh along with German and Finnish partners – includes several American students, and DEAF HEART has consequently been all over our discussions for the last year. The Europeans have been genuinely perplexed about what this term is supposed to be doing, because it feels redundant, for exactly the reason you give – if we’re talking about allyship, then we have perfectly good ways to do that already. So what does HEART add, if not a rather glib, saccharin and manufactured politicization of identity? As a professor to this group of Deaf and hearing students, my perspective is that the notion of DEAF HEART hasn’t made our discussions deeper or sharper by one iota – but it has chewed up a lot of time with positioning and posturing when we might have been getting to grips with analysis of a hundred serious problems in the field.

One Thousand thumbs-up :)

Thank you. For bringing up a topic that has been nagging me in 2014! I feel exactly the same way. I will defintely share this article with friends!

Thanks, Alison. As I mentioned to Raychelle on her Facebook page, I had originally used a different example (a male empathizing, but not understanding, in regards to pregnancy)–but when I showed it to a friend, who is Asian, she suggested that I use her culture/ethnicity as an example to really drive the point home about how absurd this comment was. So I honored her wish. I understand your perspective as a white woman, though. Even so, I will stick to what my friend asked me to do.

I’d love to see your response to Mr. Curious above.

Graham, this is by far my favoritestest response. Thanks!

This is the second article today I’ve read/watched on Deaf-Heart and what it means or should mean to the Deaf community and to hearing interpreters. I applaud your use of the term ally and I completely understand that it’s what was meant by folks like Stephanie’s mom and by the woman who started teaching me ASL when I was just 8 years old. As Andrea Smith said in her blog “Saving Lives” it’s about a beneficially mutual exchange. It’s not symbiotic, where we must have each other’s “heart”. We can survive without each other – but when we do, it’s at times more difficult for us both. Yes there are quacks (unqualified or under qualified interpreters), just as there are quacks in the field of law, medicine and other areas. There are also interpreters who are SKILLED, but not well liked by specific individuals in the community. We ALL have the right to choose who we interact with – socially and professionally. Are interpreters as a whole scorned and unappreciated? NO! I feel very appreciated and respected by the people I work with. Notice I didn’t say “the clients I serve”. Why? Because we work together. I learn from them, they learn from me. I provide a skill, they provide a venue for my skill and years of life experience that I can learn from to help make me a better interpreter. I’ll never be “D” deaf. But I can be “H” hearing – to me, that means HONOR. Honoring Deaf culture, deaf individuals and deaf ways by working together as true allies.

Very good discussion of the concept. The first time I saw the word was from a fellow Deaf person — and the reference was not related to interpreting. It’s interesting to see how the term has been taken up as a sort of “saccharine medal” by the ASL interpreter community. It’s rather normal for people who are learning a language to identify with the culture that bears the language, but when it comes to the Deaf/ASL community there are so many intersectional things that come into play. It’s sticky ground.

I’m not comfortable how things are currently framed in the interpreting profession — for all the advances we have made, the deaf consumers are still pawns. There’s a lot that still needs to change.

Thank you so much for this.

Deaf-Heart has been this giant unattainable zephyr floating about. You have it if a person who is Deaf says you have it but what about the next person you encounter who is Deaf and says you do not?

This gives me the permission I have been longing for. I am hearing. I am hearing and that is okay. I do my best each day and try my best to better my skills. I don’t have to float in the air. I just have to do my work to the best of my ability and never lose sight of the power structure and who is disenfranchised. Thank you Trudy.

This article challenges my way of thinking about interpreters in general. There are some interpreters that are more “hearing minded” than others. For example, growing up with a Deaf sister makes me more aware of Deaf cultural norms. I am more aware than other hearies and I am more sensitive to things. What I am I? AM I an ally? This is not something that I can turn on or off. Yes, I can work with the Deaf, together, which makes me an ally however there is a difference between me and a nerda who is hearing minded and not Deaf minded. Fine call me an ally but never put me in the category of a ” hearing minded” interpreter. Barf! 9 to 5 interpreters who get into interpreting because they want to “help” Deaf people and think of them as clients and would never marry a Deaf person? Barf and double barf. I know I will never be Deaf but some hearies need to get off their high horse and stop thinking of Deaf as 2nd class citizens.

I like the word “Ally”. It sounds or should I say seems humble and simple. Well-said, Trudy.

Thank you for sharing your thoughtful insight. I would never label myself as having a “hearing-heart”. The term “ally” is more fitting.

Thank you Trudy for putting words to my thoughts over the last several years. As an American interpreter living in Europe, I have been teaching the term Ally as I dislike using labels when most are unnecessary and lead to too much “interpreter-ese”. These ambiguous terms can lead to students and experienced interpreters to misunderstand the concepts that are trying to be shown by the latest word or phrase. When we use such created terminology, it puts an importance on it that many will latch onto without analyzing it’s true meaning or worth. I think this is exactly what Graham H. Turner is describing in his comment.

So very well said Trudy. As an agency, we often interview potential interpreters just getting started. This term “Deaf Heart” is a popular buzz word right now. Each new candidate feels the need to demonstrate their abilities by adding this to their skill set. Recently , a freshly graduated interpreter told us that her (hearing) instructor mentioned how a Deaf Heart demonstrates a proper balance of respect and sympathy. Sympathy? Sympathy! As Graham highlighted, poorly defined catch phrases can be easily misinterpreted.

I recently received your article on “Deaf Heart” from a deaf friend. I am an Interpreter Educator. I tell my students that one of the most important lessons I learned in the early days of my career is that I am a hearing person. That I have a place in the deaf community but I am not deaf. that I will never be at the center of their community. Part of being effective is accepting that. I also remind them that when a deaf person asks if you are hearing then says I thought you were deaf it means you did or said something that tipped them off that you were hearing. In my opinion if a deaf person wants to comment that a hearing person has a deaf heart that is ok but a hearing person should never say that of themselves. To me it is much older than 15 years ago. It basically means the interpreter cares about the deaf community and isn’t just using them to earn a living. I have most often seen it said about CODAs. Its prevalence today cheapens the term.

Trudy,

Your blogs inspire me to become a better, more humble interpreting student, but more importantly, a better human being. I have been in a bit of a crossroads lately, questioning If ASL Interpreting is the right profession for me. I have been reading a lot of negative, highly political opinions of what hearing and Deaf people believe interpreters should/shouldn’t be and I feel I am being pulled in both directions. I just want to be the best me I can be, and respect both my future hearing and Deaf colleagues. Most importantly, I just want to remember why I started this journey in the first place. I love ASL, I love the Deaf Community/Culture, and I love communicating with people. I also want to provide a service which gives equal communication access to the Deaf Community. I am just afraid that I may say the wrong thing, or that I may be too sensitive for the important job I will have to do. I want to thank you for supporting the interpreting profession. You make me feel like I can do this. All I can do is try. I’m sorry for the long rant, now about the term, “DEAF-HEART.” I completely agree with your analysis of the term “DEAF-HEART.” I have a heart for all people, Deaf and hearing alike. I value and cherish the hearing community that I grew up in. I also value the Deaf Community and ASL, which I had not had the privilege to experience until college. I always think to myself, why can’t I feel both? I know I will never truly understand the Deaf experience and that’s okay! I respect hearing and Deaf people alike. I love the point you made about being an ALLY to Deaf people. You have truly helped to reignite my passion for entering the interpreting profession, and hopefully becoming the best ALLY I can be. Thank you for kindly speaking the truth. Thank you for reading this long message; I too love to write! :-)