This article originally appeared in DeafNation Newspaper, November 1997. Read the 10-year follow-up article here.

This article originally appeared in DeafNation Newspaper, November 1997. Read the 10-year follow-up article here.

Editor’s note: TRUE-BUSINESS is an ASL gloss. The rough English equivalent is: “Is it really true?” or “Are you sure?”

One of the cornerstones of the Deaf community is the residential school.

Ever since American School for the Deaf was first founded in 1817 by Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, deaf students have been going to deaf schools.

True, these schools were often predominantly run by hearing teachers and administrators, not to mention janitors and dormitory staff.

But in the 180 years since ASD was founded, deaf people are found at every level within deaf schools. Nowadays, it seems that most residential schools are run by deaf people in every category, from janitorial to dormitory supervision to teachers to administration.

Have the times really changed? Are residential schools for deaf students now really mostly deaf-run?

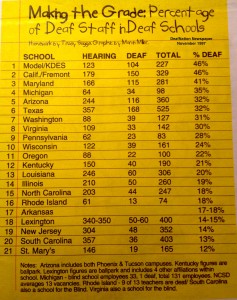

DeafNation contacted over 40 deaf schools, and got the numbers of hearing and deaf staff at various deaf schools during the 1996-1997 academic year (see graph).

From the 21 schools that responded or had the numbers available, the highest percentages were found at two schools renowned for their high rate of success in deaf students.

But even with the highest percentage, it was surprising to find that not one school that responded had a majority of deaf staff*. Many schools also refused to respond to DeafNation’s request for statistics.

The schools with the highest percentage (46%) of deaf workers were California School for the Deaf-Fremont, run by Superintendent Henry Klopping, who is a child of deaf adults (CODA), and Model Secondary School for the Deaf/Kendall Demonstration Elementary School, located at Gallaudet University.

The next highest was Maryland School for the Deaf, run by Superintendent James Tucker, who is Deaf, with a 41% deaf staff. Following that was a lower percentage of 35%, at Michigan School for the Deaf.

These numbers are startling, considering how loud the Deaf President Now movement was in 1988, and considering how the Americans with Disabilities Act has tried to provide equality in the workplace and elsewhere.

Is it a case of hiring discrimination? Is it a case of simply insufficient availability of deaf teachers and administrators? Why are there no residential schools that have a majority of staff being Deaf?

Most cited is the widening of career choices for deaf professionals. Peter Seiler, formerly the superintendent of the Illinois School for the Deaf and currently the superintendent of the Arkansas School for the Deaf in Little Rock, says, “I think we have done such a good job in opening many doors for career opportunities that teacher is no longer the only professional choice for educated deaf people. That is one reason and maybe the major reason for the low percentage of deaf and hard of hearing professional staff.”

David Updegraff, a hearing (but losing his hearing slowly) superintendent of the St. Mary’s School for the Deaf in Buffalo, N.Y., agrees with Seiler. “For example, how many deaf people 10 years ago worked as reporters for newspapers? Probably none, but there were printers. It used to be that if deaf people wanted a professional career, they almost had to work in a school for the deaf. There were always a few exceptions, like ministers or rehabilitation counselors, but the situation is radically different now. Merrill Lynch has deaf stockbrokers, an auto dealer has a deaf salesman, a law firm has deaf attorneys and so on.”

Hiring systems and pay levels were also cited as possible reasons for the low percentages, especially in state-supported residential schools. Alex Slappey, the Deaf superintendent of the Wisconsin School for the Deaf in Delavan, explains, “State residential schools tend to follow state hiring requirements. Sometimes the system will put a deaf individual at a disadvantage.”

Seiler supports this theory, saying, “Since state schools for the deaf are operated as a state agency, these schools are stuck by the state level pay grade plan. . . State legislators want to shave costs from the state budget to make the taxpayers happy and so they pick on programs with little visibility and state schools for the deaf have little visibility.”

Another major possible reason cited by both Updegraff and Seiler is the issue of teaching certification. Updegraff states, “There is still a serious problem in many states with the requirement that teachers pass the National Teacher Examination to get certified. That is a tough exam for many people to pass, including deaf and hearing people, but deaf people have a tougher time than hearing because of the structure of the exam.”

Seiler concurs. “These tests often stress speech development rather than language development or communication development. These tests are also culturally biased towards hearing people and away from the deaf people.”

Just how this disproportionate number of deaf staff affects the heart of every deaf school—the students—is a key question in many superintendents’ minds.

David LeFors, who worked at the Louisiana School for the Deaf in Baton Rouge from 1992 to 1994 as a dorm counselor, says, “The kids would always come to me or other deaf counselors, because they were more comfortable to talk with us and because they could communicate with us without having to repeat or slow down. They seldom went to the hearing counselors because they didn’t see much support or bonding from the hearing staff.” LeFors left LSD to take a better-paying job.

Brian Sipek, a junior at the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville, recognizes this comfort level with deaf staff, also. “The [hearing] staff are usually not familiar with what the student needs, being a deaf person. There are some hearing teachers, I admit, that try to be very helpful to deaf students, but it’s not the same coming from them, since they were never raised as a deaf person. They’re just not as familiar with being deaf as we are.” Sipek is third-generation Deaf.

Slappey says, “I believe the outnumbering of hearing staff also affects the level of language interaction with the children. They have less exposure to fluent ASL through native users.”

Dr. Ernesto Santistevan, a hearing clinical psychologist at the New Mexico School for the Deaf, admits the limitations of being a hearing person at a deaf school is quite powerful for the students. Even though Santistevan is quite fluent in ASL, having earned his degree in Gallaudet University’s five-year doctoral program, he says, “I don’t have that effortless communication and knowledge of culture a CODA or a Deaf person would have. It impacts service and I believe anyone who says it doesn’t is fooling themselves.”

Santistevan adds, “I think it affects the kids because it is hard to find Deaf role models in high stations.”

When asked how to solve this disparity in numbers, Slappey mentions that aside from increasing pay scales for deaf workers commensurate with their position’s responsibilities, “I also think we need to get more deaf adults interested in teaching as a career.” He cautions, however, “What I don’t think we should do, is hire the deaf just for the sake of having deaf staff in positions. If they are not qualified, if they are not the best applicants, then we are ‘watering down’ the quality of our program and that is not in the best interests of our children.”

He also states, “I think it affects the students in the sense that they continue to see the deaf as a less powerful minority. I think it sends a message that does not help the self-esteem of the deaf.”

There appears to be a long list of questions surrounding this issue. Schools must take into consideration whether it is better to hire hearing individuals who are overqualified for their respective positions, or to hire qualified deaf people who have experienced deafness their entire lives. Are schools responsible for not having enough deaf role models? Or is it today Deaf people choose to work in fields long dominated by hearing people? Are Deaf graduates of deaf schools giving back to their schools in various ways, whether it be teaching or simply attending football games?

How do schools address this problem of having a large inequality in deaf and hearing staff, when language is so essential to the child’s learning process? Since deaf schools have a majority of hearing staff, does it mean the hearing staff is to blame for the national reading average being at third grade for the deaf individual? What does it all mean for the student?

Ronald Sipek, Brian’s father and also a graduate of the Illinois School for the Deaf, says, “I can’t imagine what it is like for those students to have limited deaf role models. It is so important for them to have teachers and workers that they can go to who will understand their deaf ways, their communication, and their experiences, because they have, too, experienced it themselves. Brian has a Deaf family. But what about those who are not from Deaf families? Who do they look up to if there are not enough deaf role models at the schools?”

* The word staff includes those employed at every level, including janitorial, administration, teaching and support staff.

Read the 10-year follow-up article here.

Copyrighted material. This article can not be copied, reproduced, or redistributed without the express written consent of the author.